You know, everything

Elissa Steamer finally gets a cover.

Not that it should be surprising, given the way things are and the way things were, but it did cause my eyes to widen and an involuntary jeez to slip past my lips when a series of Instagram Stories1 informed me that professional skateboarding icon Elissa Steamer, in her nearly three decades on the job, had never been on the cover of a major skateboarding magazine. I learned this at the same time that condemnable omission (perhaps even a misdemeanour or felony of some sort) was rectified when, in the first few days of 2024, the last remaining major skate publication, Thrasher, posted a photo online of Steamer holding a photo of herself on the cover of their magazine.

It was a genuinely wonderful moment and the reaction from friends and fans online reflected as much. Steamer is the rare person you can heave the heady, often misattributed title of “legend” onto, and it doesn’t feel like hyperbole or lazy genuflection. She’s a figure whose credentials deserve celebration and then some. There’s her catalogue of video parts, from Toy Machine Skateboard’s Welcome To Hell (1996), Bootleg’s Bootleg 3000 (2003), Six Newell (2004), and all the way up to Nike SB’s Gizmo (2019). She was the first woman to have a signature skateboarding shoe (the Etnies “Albatross”), won a grip of X Games medals (four golds, one silver, and a bronze), and became a legitimate household name thanks to her appearance as a playable character in the Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater video game franchise. That’s a resume on par with any of the industry’s biggest names. It’s what has made her an inspiration to untold millions of skaters around the world.

Steamer finally getting her first cover feels like a historical wrong made right. Yes, we know the way things are and the way things were, but as she nears 50 years old, you still have to wonder how the skateboarding industry’s media apparatus could have overlooked Steamer in this way for so long. How it could miss — or dismiss — what has always been right in front of us.

To say that someone “deserves” something is often portrayed as a tough sell in an industry as fickle and mercurial as professional skateboarding. This is, after all, a business where the livelihoods of sponsored “riders” or “athletes” are decided by marketing strategies and budgets, not merit. It’s a cruel, capitalist reality that reaffirms itself in the culture, often by the people who shape it. One of Jake Phelps’ more famous Phelpsisms is that "Skateboarding doesn't owe you shit. It owes you wheelbite in the rain." That’s the late editor-in-chief of Thrasher Magazine, which has given out a trophy once per annum since 1990 for who it thinks is owed the title of Skater of The Year.

So, this idea of what is earned and owed in skateboarding is more than a bit confused and arbitrary. We’ve spent years being told and telling ourselves in kind that a lifetime of dedication, impact, and influence is just a nice-to-have, not a thing we should cherish and uplift in any meaningful way. That professional skateboarding, like youth, is fleeting, and those who reach that level should just be grateful for their time spent on board.

A little conspiratorial ball of red twine sits at the back of my brain and begins to unwind whenever that sentiment surfaces. In retrospect, it seems like a purposeful devaluing of labour dressed in some half-baked pseudo-punk nihilist ethos. Because, of course, professional skateboarders are “owed” something for their skateboarding. They are the tools companies use to market their products and whatever success they bring keeps the industry afloat. That marketing subsequently keeps skateboarding media outlets alive as companies buy ad space in their magazines or websites to sell products via those skateboarders. Everything hinges on the skateboarders. They are owed everything. If not for them, we’d all be riding Wet Willy and Flameboy graphics.

It’s simply a matter of choice who skateboarding — its industry and media — chooses to highlight or, more accurately, market. To continue using Thrasher as an example, according to their archives, there are, as of their March 2024 edition, 527 issues of the magazine, including one-offs like their 1988 “Collector’s Edition” and “Skate Rock” issue in 2012. If you include alternative collector’s edition covers like Mark Appleyard’s dual covers in 2001, the five Pretty Sweet commemorative covers for the January 2013 issue, the four “Biggest Tricks of 2014” collectible covers for the January 2015 issue, and the alt Dylan Rieder memorial cover for the January 2017 issue, there are a total of 536 Thrasher covers.

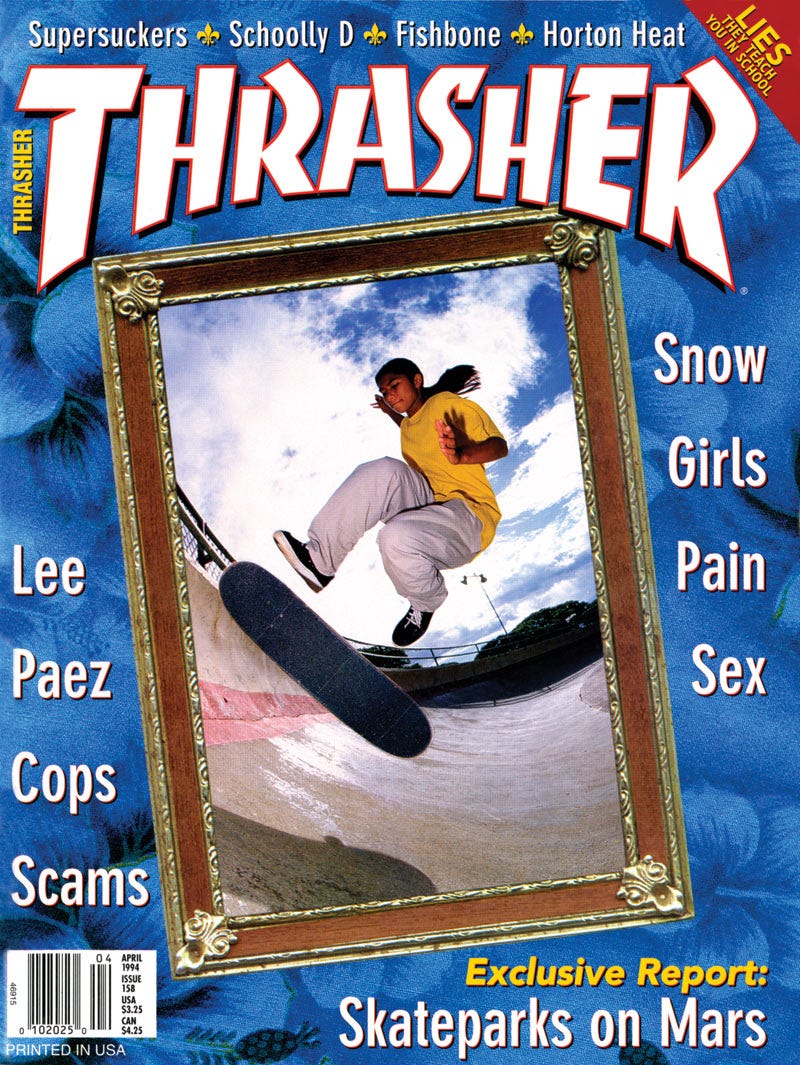

Of those 536 covers, only eight have a woman skateboarding on them. There are more illustrated covers (nine) than that. Danzig of Misfits fame got a cover (June 1986) before the first woman did (Cara-Beth Burnside, August 1989). Nearly a half-decade later, Jaime Reyes would wind up on the April 1994 cover. It would be 23 years before Lizzie Armanto repeated the feat in May 2017. Four and a half years after that, Breana Geering would front the mag (October 2021), and since then, there’s been at least one woman on the cover per year (Samarria Brevard, January 2022; Funa Nakayama, January 2023; Nora Vasconcellos, October 2023; Elissa Steamer, March 2024).

With five of eight of those covers coming in the last two and a bit years, it’s clear that Thrasher’s leadership is finally recognizing and supporting women’s skateboarding in a way they haven’t with any consistency before. While a magazine cover might seem trivial in the larger sense of supporting women in skateboarding — that ideally would continue to include more sponsorship opportunities, more substantive coverage across the board, and a culture shift to create a more welcoming environment in a traditionally and aggressively male-dominated space — it’s still a promising sign.

This isn’t a reality that only Thrasher has had to grapple with and learn from; the industry as a whole has never given women their due. TransWorld Skateboarding, once Thrasher’s main competition in the field, would only ever have one woman on the cover of its magazine in its nearly 36-year history (Lizzie Armanto, November 2016) before ceasing print editions in 2019. While there has been significant progress in recent years, most skateboarding brands’ teams still don’t have any women (or queer, trans, or gender-non-conforming people) on them. And if they do, having more than one is even rarer. (Etnies’ recent tour video, Barge The Bloc, featured four female team riders, a legitimately surprising and welcome sight).

Decision-making like that overlooked entire generations of talented skateboarders and created a self-inflicted yet easily avoidable catch-22: If women couldn’t get coverage, they likely wouldn’t get sponsored because sponsors want you to get coverage. However, the companies that sponsor skateboarders are the ones who put out videos and purchase ad space in magazines and could’ve supplied that coverage themselves. If the industry had wanted to cater to and support women in skateboarding, they could have done so then like they’re doing now. But they didn’t. And there was no real reason besides obvious, hamfisted, lunkheaded sexism.

In Steamer’s Epicly Later’d episode from 2012, Zero Skateboards owner Jamie Thomas talks about the perceived struggle in selling Steamer to the purchasing public while she was on Toy Machine in the 1990s and promoting women in skateboarding in general.

“It’s challenging marketing a girl to guys. Normally when you buy someone’s crap, it’s because you want to be like the person, or you look up to them, or you want to skate like them. Most teenage boys probably don’t want to skate like a girl, even though [Steamer’s] badass and the best girl skater.”

“The best girl skater.” Does skating a board with a woman’s name on it make you skate like them? What is “skating like a girl” anyway? Do boobs grant access to different tricks? These are tired semantic arguments by this point, but this siloing has always been the issue. It’s not exclusive to skateboarding by any means; fixed gender roles are the goal of a patriarchal society. That has long steeped our wider culture in stereotypes that industry jamokes would come to see as limiting to marketing potential for women in sports at large.

That dullard’s viewpoint is why the WNBA was used as a punchline for years. But once the league secured a decent broadcast deal with ESPN and more substantial financial backing — which allowed space for its athletes to grow and made its games more readily accessible to audiences — people started to tune in and enjoy the next-level talent and athleticism on display. The league has since taken off, with 2023 being its most successful year on record and expansion teams on the way.

In skateboarding, that historical lack of industry or financial support forced women to create their own companies and media outlets, like Rookie, Meow, Villa Villa Cola, Yeah Girl Media, Quell, and many more. It also made whatever coverage women skaters did get something of a rarity. Womxn Skateboard History, the project of skateboarder, writer, and librarian Natalie Porter, looks to document the skateboarders and women-fronted projects from the 1960s to the present day that might have otherwise been lost to time. It’s documentation of decades' worth of passion. Places earned. Influence spread. Impact made. In Porter’s library, you’ll find the names of skaters like Stefanie Thomas, who most won’t recognize but did infinitely more for skateboarding than Glenn Danzig ever will.

The not-haha-funny part of it all is that if the skateboarding industry had clued in sooner, had decided to invest in women, to sponsor and promote them, it would’ve opened up an entirely new market to sell their crap to. A market that is now bigger and more vibrant than ever, without much thanks to the mainstream industry. Helped along by the advent of social media, grassroots organizing, and wide funnel events like Women’s Olympic Skateboarding, the number of women in skating has skyrocketed. Mariah Davenport’s “2021 Skater Representation Survey” of over 2,200 skateboarders in the United States found that 43% of respondents identified as men, 32% as women, and 25% as gender-non-conforming.

Even at that sample size, those numbers jump off the page. Davenport breaks down the data further to find that in the last decade, the participation rates of women in skateboarding have jumped 790% (in contrast to a 47% decrease in men’s participation).

Davenport attributes that growth to “The ability for women [and gender-non-conforming skaters] to find representation for themselves on social media platforms to compensate for the lack of representation in mainstream media. Women and GNC skaters were finally able to see themselves in the act of skateboarding and building community to support one another’s progress from a distance.”

Through those social media platforms, “on-the-ground organizations and meet-ups” connected new and prospective skaters online and then in person. Davenport credits those like “Skate Like A Girl, Exposure Skate, Lisa Whitaker, Briana King’s Meetup Tour” and more for laying the groundwork, noting that each “were teaching, advocating, filming, and organizing in order for more women to have access to the sport of skateboarding.”

Following that continued and sustained growth in the number of not just women but queer, trans, and gender-non-conforming people across skateboarding in recent years, companies finally began to realize they could profit off of the followings that people in those communities had built. While bleak on its face, that is the reality for anyone attempting to break through as a professional skateboarder. Your audience is an asset. You are a marketing asset. Along with the slow, progressive shifts in broader society, this has had the effect of making the mainstream industry more inclusive, which is good, but it’s important to recognize that change is built off of the work of those grassroots efforts to foster and provide a platform for “non-traditional” skaters.

That’s just progress, such as we know it.

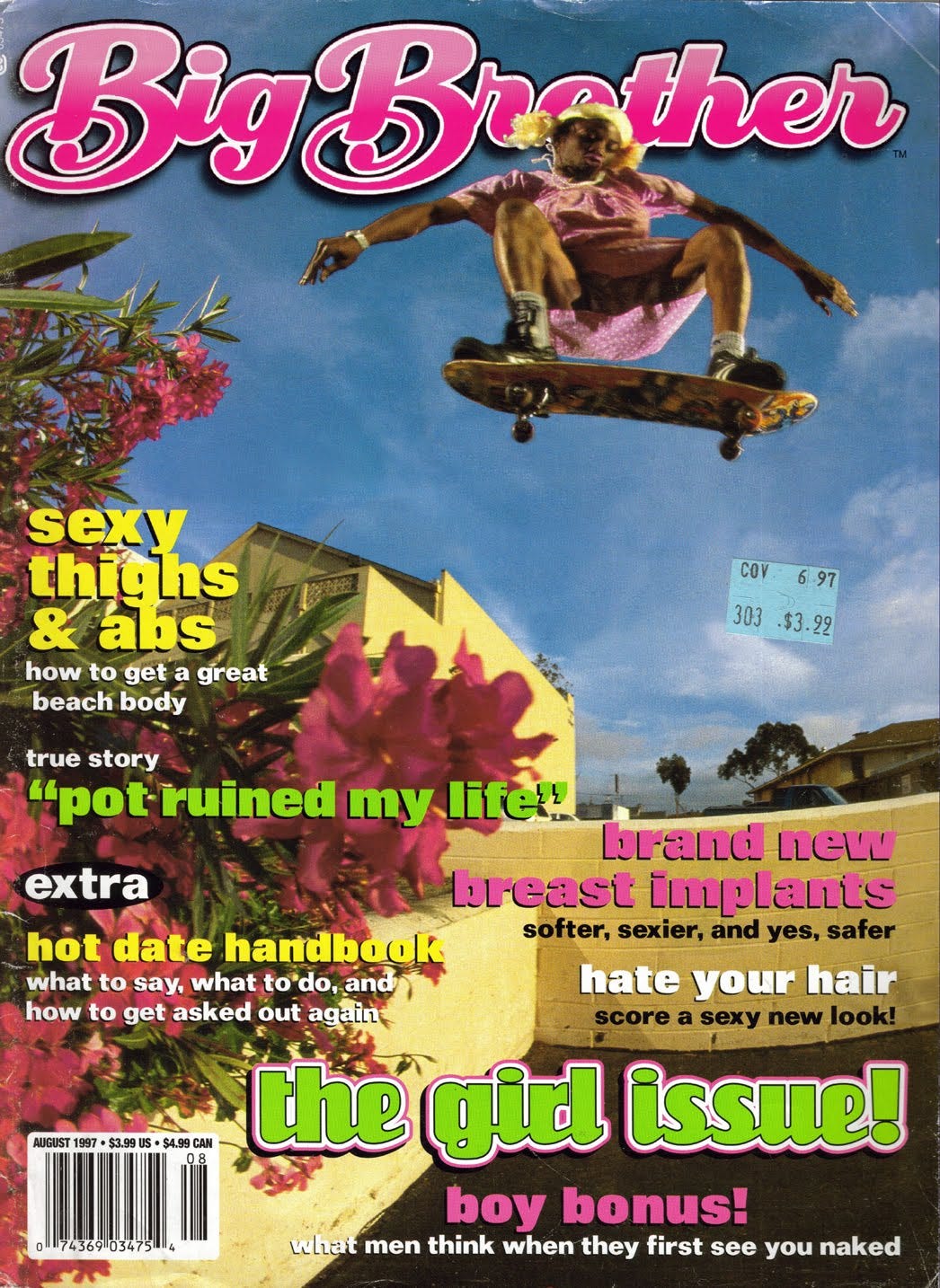

Twenty-six years ago, Elissa Steamer had her first opportunity to grace the cover of a major skateboarding magazine. As she’d tell Patrick O’Dell in her Epicly Later’d, Big Brother wanted to put her on the front of its August 1997 “girl issue.” It came with a catch.

“They wanted me to shoot the cover in a dress, and they offered me like $1000, too.” Steamer would ultimately turn it down but wasn’t sure if she’d made the right call for her career. “If they’re not going to give you a cover for being a good skater, then fuck it. You don’t want to kook it out.” Ed Templeton would tell her. Clyde Singleton eventually took her place.

“Thinking back on it, it wasn’t such a big deal, but I was like, ‘I’m not compromising my integrity.’” Steamer told O’Dell. It was a big decision for someone in their early 20s to make, for someone trying to make it in an industry that showed little interest in having her in it. That integrity and authenticity are part of what makes her the legend she is today.

At the time of her Epicly Later’d feature in 2012, Steamer had found herself nearly sponsorless and at a crossroads. She’d quit Zero after not getting the support she felt she deserved and came to accept that her career was winding down. “It’s hard to say goodbye to something… nobody wants to let that go.” She’d say as she readied to do just that. Mike Maldonado, her former Toy Machine and Bootleg teammate, couldn’t understand how her career had wound up in such a place.

“She’s the best female skateboarder, period. And beyond that, she’s one of the best skateboarders. I don’t see why she don’t have her own damn soda, amusement park, video game — you know, everything.”

Everything is the least Steamer deserves for what she’s accomplished. For what she’s brought to skateboarding. Eventually, skateboarding began to acknowledge that, too. She’d go on to secure roster spots with Nike SB and Baker Skateboards. Nike would release Gizmo, a video bearing her nickname and celebrating her legacy. She’d get inducted into the Skateboarding Hall of Fame. Then, the skateboarding world would collectively revel in a photo of Steamer holding a photo of herself on the cover of a magazine.

While it took almost 30 years and all that’s happened in between, it seems like everything is finally what she’s got.

Shoutout to The Secret Tape.